A Pathan with a pen

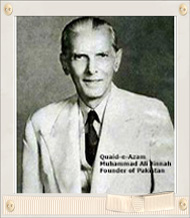

GOOD LORD! Exclaimed the Quaid as he entered the drawing room of Mian Bashir Ahmad´s residence at 23 Lawrence Road, Lahore, where my father, Maulvi Muhammad Yakub Khan, editor of The Light, had been invited by Mian Sahib to meet the Quaid at the latter´s request.

“I was expecting a smartly-dressed man from Oxford, judging from your writings, and here you are a Maulana! You have certainly given me a surprise.”

It was the autumn of 1942, if memory serves. Father had gone to see the Quaid in his usual clerical clothes – a long coat buttoned up to the neck, a matching pair of trousers, a Jinnah cap and of course, a beard.

It was a signal honour. Many people wanted to meet the Quaid, but the request from the Quaid, that he wanted to meet the editor of The Light, was an honour conferred in recognition of the yeoman´s service that The Light had rendered to the cause of the Muslim League.

According to Mian Muhammad Shafi, the veteran journalist, `Your father was the first man to support the Quaid in the columns of The Light in the Punjab, right from early 1936. The rest of the Punjab press was either hostile or indifferent`.

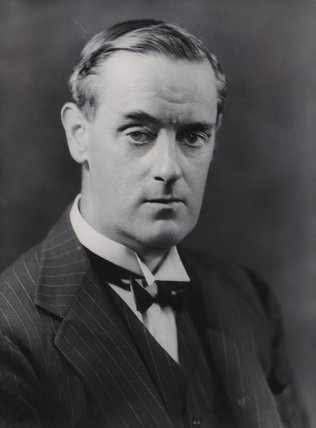

Later, at a tea party hosted by Maulvi Muhammad Ali, the famous translator of the Holy Quran into English, the Quaid made a short speech in which he recounted his association with and attachment to The Light. He not only read every issue thoroughly, but also kept a file of the paper, he said. To illustrate how The Light had helped in his work of advancing the Pakistan Movement, he recounted an encounter with the Viceroy, Lord Linlithgow, in the following words:

After I had first propounded my two-nation theory, the Viceroy said to me, “Mr. Jinnah, I had always thought you to be a sensible and intelligent man… But, now that you have come out with this new-fangled theory, I have my doubts.”

`I told him I would send him an editorial of The Light on the India`s Two Nations. He was to read it and let me know his reaction. A few days later I received a note from Lord Linlithgow saying:

“Now I see your point of view.”

(Lord Linlithgow`– Governor-General and Viceroy of India from 1936 to 1943)

Here is another instance of the importance the Quaid attached to The Light – Aziz Baig, in his Jinnah and His Times (Page 35), writes:

Jinnah dealt so honestly and honourably with his people that, on more occasions than one, he took decisions which a typical politician would regard as insane and unnecessary. In the mid-Forties, the Muslim League ministry in the North West Frontier was toppled: The Light, a fortnightly journal from Lahore, not widely circulated, published a news item with the slant that it fell because it was corrupt. I was then a senior assistant editor and leader-writer with Dawn in New Delhi. I was rather astounded when Jinnah´s junior secretary met me and told me that Jinnah wanted this story to be reproduced in Dawn. Jinnah was the president of the Muslim League and Dawn, under his patronage, was the only first-class daily paper of the Indian Muslims, tacitly supporting the policy and programme for the freedom party. Why should Dawn bring into disrepute its own men, and why should we proclaim and publicise the face that, given a chance to rule a province, the Muslim League betrayed the trust reposed in them? I didn´t take the risk and phoned Jinnah late in the evening at his New Delhi residence.

I was about to broach the subject when I heard Jinnah telling me forthwith that the news item should appear in Dawn. This was Jinnah´s standard of probity. The moral is plain: he didn´t want to hide anything from his own people. If the people trusted the leader, the leader must trust the people and tell them the truth.

This also shows the trust the Quaid put in the editor of The Light: if he said that the ministry was corrupt, it must be true.

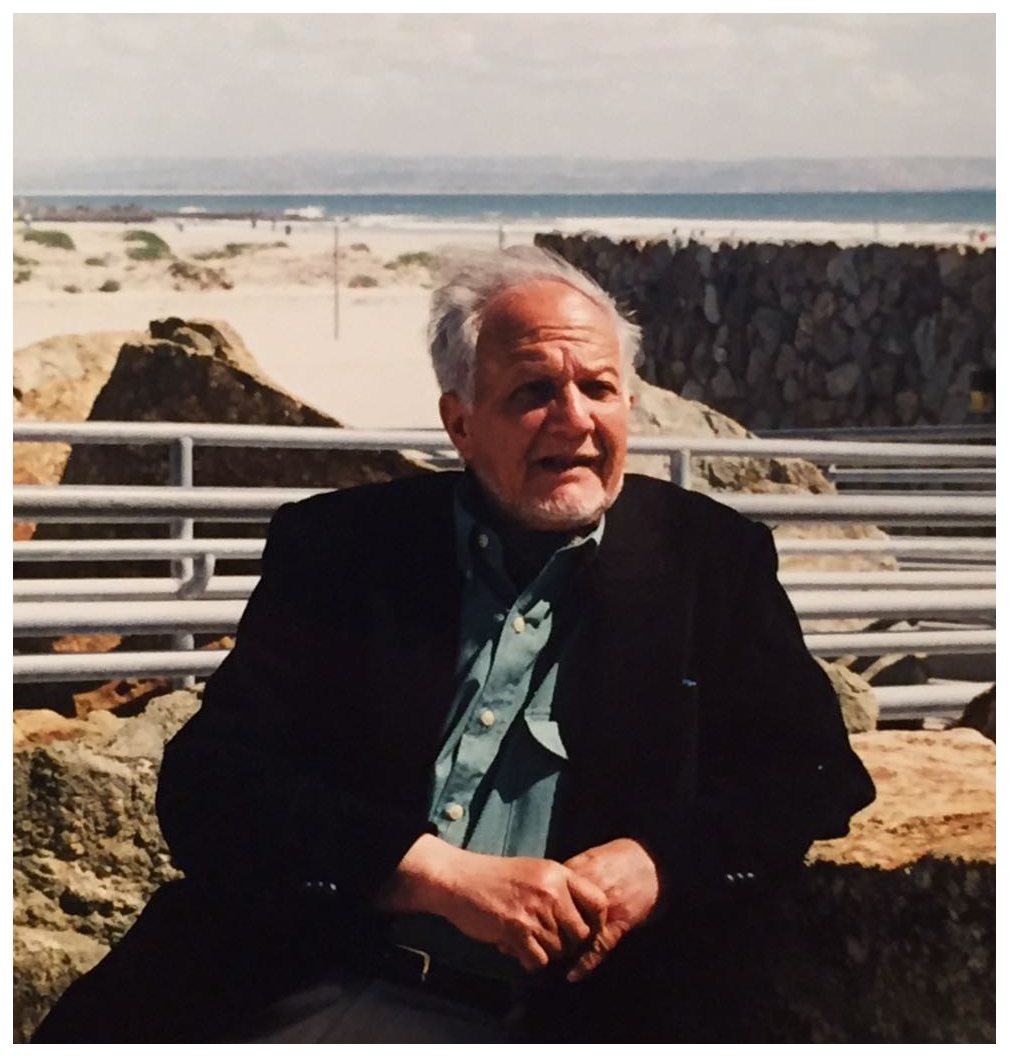

What sort of a man was this Maulvi Muhammad Yakub Khan, who had captured the respect and esteem of the Quaid? Since he happens to be my father, it is a difficult assignment, for I could be accused of shouting Pidram sultan bood! But for the sake of the coming generations we must recapture the life and times of those who gave their best to the Pakistan Movement and to the Musalmans of the subcontinent.

Origins

Nestling at the foot of the Pabbi Hills, a few miles from Nowshehra on the Noshehra-Peshawar Road, lies the little village of Pir Piai (the village of pirs). It is a neat and clean village, and probably has the highest literacy rate in the province. To its people it is also known as `Little England`, owing to its love for education and all things modern – a signboard at the junction of the Grand Trunk Road and the kacha road leading to the village used to boast: `98 men served in the World War from the village`.It also boasts of having produced a few generals, a former governor of the province, a film actor and quite a few bureaucrats and educationists.

Nestling at the foot of the Pabbi Hills, a few miles from Nowshehra on the Noshehra-Peshawar Road, lies the little village of Pir Piai (the village of pirs). It is a neat and clean village, and probably has the highest literacy rate in the province. To its people it is also known as `Little England`, owing to its love for education and all things modern – a signboard at the junction of the Grand Trunk Road and the kacha road leading to the village used to boast: `98 men served in the World War from the village`.It also boasts of having produced a few generals, a former governor of the province, a film actor and quite a few bureaucrats and educationists.

Father´s clan, the Babers, left Afghanistan probably in the 17th.century and settled in the northern portion of the village. And in this village, in a Log-and-Mud cabin, father was born to Mir Alam Khan and his wife on 18th. September 1891. Littles is known of his childhood, except that apart form being a good scholar he was a good sportsman. He graduated from Islamia College Lahore and also had the distinction of captaining its football team. After passing the B.T. course he was offered government service as an assistant inspector of schools, but the promising worldly career was not to be.

`I saw myself lying in the grave, ` father would say, recounting how he decided to devote his life to the service of his religion and to his people, `and a saintly figure appeared and said to me, “Arise and wage jihad with the pen.” This vision was the turning point.

For sixty years, till December 7, 1972, the date of his departure from this world, he wielded his pen in the way of Islam and his fellow-men. As editor of The Islamic Review-London, The Light- Lahore, Muslim Revival- Lahore, and later The Civil and Military Gazette-Lahore, his pen waged a relentless jihad.

Personality

His personality is best summed up in a farewell note published in The Islamic Review of England in its issue of October 1923: –

With the departure of Maulvi Muhammad Yakub Khan, who left London on September 20, 1923, en route for India, the Muslim Mission in England loses, for a time only, we hope, a tireless worker, a skilful leader and a unique personality.

The two years of his Ministry in this country, brief as the period may seem, have been of outstanding value to the work of the Mission, and

have left behind them a mark, it may also be said, which will not easily be affected or forgotten.

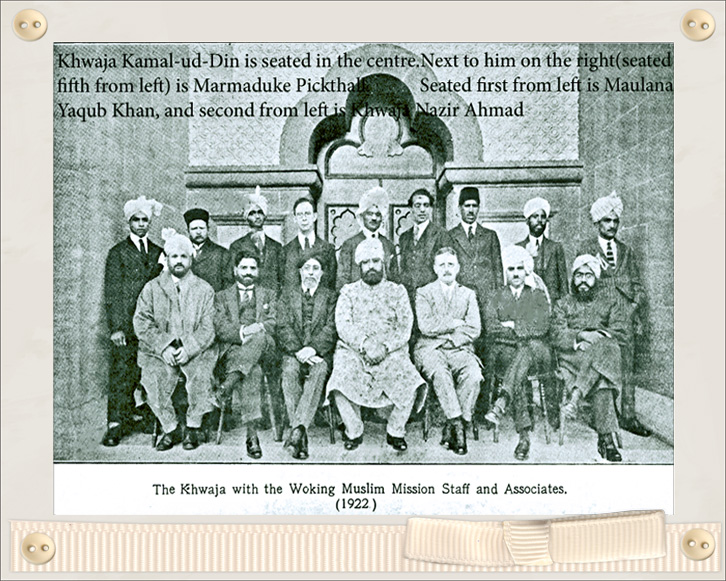

Maulvi Muhammad Yakub Khan left the Government Service at the call of Spiritual duty in 1919, resigning a lucrative position to devote himself heart and soul to the cause of Islam. In 1921, he came to England, where his ripe scholarship and wide experience in affairs was especially welcome. He took over the conduct and management of the Islamic Review together with the Publication Department of the Mission and had charge, for a year, of the London Prayer House at 111 Camden Hill Road, Notting hill Gate. During his stay he translated Seerat-a-Khairul-Bashar (The life of the Holy Prophet) by Maulvi Mohammad Ali, and the Secret of Existence by Khwaja Kamaluddin.

When Khwaja Kamaluddin left England for Mecca and the Eastern tour in June 1921, Maulvi Yakub Khan assumed control of the Mission, and his peculiar fitness for that somewhat delicate post became at once apparent.

To the single-mindedness and devotion, without which no high cause may hope to prosper, must be added the wisdom of the serpent and harmlessness of the Dove: a mastery of the myriad weapons of theological warfare and an infinite tact in using them: a wide knowledge of men and affairs: alertness to discern occasion and to grasp opportunity, and the ability not only to grasp both sides of the question but also to demonstrate clearly and convincingly where the other side is wrong: infinite patience, infinite sympathy and infinite understanding…Looking back on his life and work among us during the past two years, to say that Maulvi Yakub Khan possesses all these qualities to signal degree, is not to say a word too much.

A profound Thinker, a cogent Preacher, and an illuminating Conversationalist, he based his instruction not on reason only, but on reasonableness, which is, to many, a quality at once more appealing and more human: his inflexible principle never showed a taint of bigotry, and his devotion to the faith was compounded with wide tolerance and God-begotten charity, which are of the very Essence of Islam. Argument from his bore with double force because it was untouched by Rancour: and his calm and eminently logical personality had a subduing influence on the adversary, which eliminated all bitterness and compelled contemplation.

`He made men think`… there is perhaps no higher tribute that his fellowmen may render to a servant of the Most High.

Maulvi Muhammad Yakub Khan possesses, moreover, that rare quality disguised and obscured nowadays by the over-worked phrase, `A Sense of Humour` – a precious gift of which is claimed by all men yet vouchsafed scarcely to one in a thousand. And it is this Gift of Self-Detachment – by virtue of which, had it been so ordained, he might, one feels, have aspired to emulate the achievements of a Dickens or a Gilbert – which enabled him always to take the level view in practical matters and to discharge the delicate duties of his responsible position with unvarying and conspicuous success.`

To the above must be added the pride in his pen and his absolute determination to safeguard its sanctity. Nobody could induce him to write anything which was not the truth.

To illustrate, once the owner of the C&MG wanted to mount a campaign against Dr. khan Sahib, the then chief minister of West Pakistan, for some ulterior motive. When he could not persuade father to take up the pen against Dr. Khan Sahib, he ordered a sub-editor to write the editorial, which was duly published. But father at once had a clarification printed in the Pakistan Times that the said editorial was not written by him.

Educationist

He was not only a missionary and a journalist but an eminent educationist as well. As head of the Muslim High School, Lahore, he was the first man to ban all corporal punishment in the school.

I think it was in 1912, when father was teaching in the famous high school at Qadian (India) where Allama Iqbal had also sent his son for schooling that Dr. Farid Baksh of Chak No. 333 (near Faisalabad), in whose honour President Zia-ul-Haq recently changed the name of Toba Tek Singh to Faridabad, went to Qadian and started a sit-in, even threatened a hunger strike, to persuade father to go with him and take charge of a one-room village school. Meem Sheen has recounted the incident in his column `Meem Sheen Ki Diary` in Nawa-i-Waqt recently (7th.February 1987). He went on a salary of nil rupees per month, food free and started to teach.

The school prospered and later became a college. When it was upgraded to college in Ayub´s time, father was invited to speak at the opening ceremony. ‘He just stood there and cried `, one of his pupils rang up to Meem Sheen. ` He was so overcome with emotions that he could not say a single word. `

In later years Dr. Farid Baksh would often come and stay with us at Lahore and recount past incidents. `We learnt the meaning of Khudi from Khan Sahib`, he would tell us. Dr. Sahib was invited to the UK by father in 1959 when father was once again the head of the Woking Mission, and went around with him to far corners of England to collect thousands of pounds for the college from the old boys. Dr. Farid was in his nineties when he undertook the trip.

Yes, Maulvi Muhammad Yakub Khan was a Pathan with a difference. Unlike his war-like tribe, he was a Pathan with a pen, and one of the few Pathans who bade farewell to their own beloved region to serve the people of the Punjab. Yet I am sure his heart was always with the Pathans. His emotion-charged pamphlet, The Frontier Tragedy (23 April 1930), written after the firing on the Red Shirts, was distributed in the House of Commons in London and caused a stir.

Incarceration

In the late Twenties, following the death sentence to Ghazi Ilam Din Shaheed, who had killed Raj Pal, the author of sacrilegious book Rangila Rasul, father wrote in The Light a scathing denunciation of the Hindu mentality and warned them that as long as the Hindu dragon continued to display its vile teeth, there shall always be Ilam Dins to pull out the dragon´s teeth. This was construed as an attempt to further incite violence and a suit was brought by the Hindus in Lahore courts and father was asked by the judge to apologise, which he promptly refused to do. He was sentenced to two years in the prison. Ilam Din and father, the two defenders of Namoos-e-Rasul, now lie buried only a few yards apart in the Miani Sahib Graveyard (in Lahore).

He understood Islam to be the most tolerant and human of all religions and brooked no narrow-minded interpretation of Islam. In Woking, he would often remark `What Islam can I teach to these Britishers? They have more Islam than us. Here in England, if a dog is lying on the road, people would carry him to a hospital…whilst in our country, they would not even attend to a human being in such a situation`.

Tragedies

Mother was paralysed in 1929, and father looked after her full forty-three years, never re-marrying, although he was in his prime of life at that time. My elder brother, Saleem, died of typhoid whilst in the first year in Government college, Lahore. The editorial titled Saleem that father wrote in The Light in memory of his son shall always stand as a piece of great literature. It makes us feel the sorrow of a father at his son´s untimely death. A brother and our only sister were afflicted with life-long illness. Yet he never flinched.

To quote his will, `May God grant us strength to bear the life-long affliction which we have been going through and I take it as opportunity to cheerfully carry the cross, which in God´s inscrutable ways, is always the only way to self-purification and self-dedication to a Higher Cause. `

To me he epitomises the complete True Man. His pen was never for sale. His Khudi (self-reliance, self-respect, self-confidence) was exemplary, his Tawwakal (perfect trust in God and reliance on Him alone) proverbial. He had the patience and fortitude of Job.

When God wishes to bring about a new change in a nation, he creates people who rally around the leader to bring about the change. I believe there were hundreds of such men who rallied around the Quaid… and father was one of them.

(Published in The Frontier Post – March 6, 1987)