Tolstoy and Muhammad ﷺ

There is a type of heroism which has a peculiar fascination for human imagination – the heroism of humility and self-abnegation. Gautam Buddha, Jesus Christ and inspired by these ideals, Tolstoy of a generation ago and Gandhi of our own day are the prominent figures crowned as such heroes. Buddha is moved to the very depths of his being at the sight of human sorrow and suffering. In the dead of night, he bids farewell to his palace, his lovely consort lying asleep and his pretty new-born babe and turns his back at this wicked world which has nothing but pain, sorrow and suffering for man. He seeks relief, light and nirvana in the solitude of woods and wilderness. Jesus Christ looks the very personification of this sort of virtue. His brief life is one continuous song of human love of fellow-feeling and of brotherhood. From his lips fall the choices of pearls such as “Love thy neighbours as thyself” and “Love thy enemy”. And for these ideals, he wears with a smiling face a crown of thorns, praying for the forgiveness of those who put him on the cross. Tolstoy of Russia was fired by these very ideals and from a blue blood Count and big landlord adopted the plain life of a simple peasant, a scythe, a rake and an axe being all the furniture of the uncarpeted room of this once mighty aristocrat. And Mahatma Gandhi of our day in his home-spun, home-woven Khaddar, loincloth, shirt and cap needs no introduction.

We are not so inhuman as not to be touched by the simple dignity of these lofty souls. Nor are we of those who think that this was only the height of pride that put on the mask of humility or that their “humility strutted like a peacock”. We take our hat off to souls so overflowing with the milk of human sympathy. They all present a picture so supremely sweet that in the enjoyment of the main view, we have neither the attention nor the heart to detect in the background some small, unseemly dot here and there. Gautama turns his back on the world. Grand! But along with the world he turns his back on the suffering humanity that has aroused him to such sympathy as well as the pretty girl to whom he had pledged his word to be consistent companion for life and the pretty babe he has been the cause of bringing into existence. Jesus in his excessive zeal scorns to stoop to human companionship, take a companion of life and show to the world how to bear the burden of a married life. He even forgot to keep in his heart, side by side with humanity at large due room for his own mother whom he neglected. These are the dots we mean. Of such dots, a paper from London reveals somewhat conspicuously in an otherwise ravishing picture of Tolstoy. It quotes at some length from his own wife´s Diary. Under the date January 6, 1895, she complains that it is 1 A.M., and she and the butler are waiting up for Toslstoy´s return from some committee meeting or other, where “they just talk”! She goes on to complain: –

And at eight tomorrow I will have to get up and give Vanja his quinine and take his temperature – while he (Tolstoy) will go on sleeping. And then he will go out and carry water without even asking how the child is and whether the mother is not too tired with all these cares. How very little kindness his family gets from him! He is austere and indifferent. And his biographies will tell of how he helped the labourers to carry buckets of water, but no one will ever know that he never gave his wife a rest and never – in all these thirty-two years – gave his child a drink of water or spent five minutes by his bed-side to give me a chance to rest a little, to sleep or go out for a walk or even just recover from all my labour.

This naturally takes our mind back to another picture. The Prophet Muhammad ﷺ was certainly a far busier man than Tolstoy. A lawgiver, a reformer, a soldier, a general, a preacher, a statesman, all in one, he yet had time and attention for the smallest details of duty. Rather than neglect his home people, he actually helped them in such ordinary domestic duties as cooking, sweeping the house, milking the goats and carrying water. His virtues are well balanced virtues, unmarred by the aberrations of one-sided extremism. Gautama spurned at the throne to get rid of worldliness. Muhammad ﷺ sat on the throne and yet lived the simple austere life of Buddha of the woods. Like Jesus he forgave his enemies, not merely by the word of mouth but in fact, yet he had the balance to show due respect to his foster mother who called on him in later life. Rather than snub her off with “What have I to do with thee” he exclaimed at her very sight, “My mother! My mother!”, stood up to greet her and spread his own mantle to seat her. Like Tolstoy, he lived and worked for the poor and even prayed that on the day of Resurrection, he might be raised in the midst of the poor. Yet he had not the self-forgetfulness of Tolstoy to ignore his own wife and children. “The best of you”, he taught, “is the best of you in his treatment of his wife.” Paradise, he said, lay at the feet of mothers. His wife, rather than complain of any austerity or indifference which he had none was the first to accept his message and thus testified to his loftiness of character: “You are hospitable to the guest and kind to your relations and kith and kin. You help the needy. God will never let you meet with failure.” At the death of his son Ibrahim, his eyes shed tears like a loving father.

This naturally takes our mind back to another picture. The Prophet Muhammad ﷺ was certainly a far busier man than Tolstoy. A lawgiver, a reformer, a soldier, a general, a preacher, a statesman, all in one, he yet had time and attention for the smallest details of duty. Rather than neglect his home people, he actually helped them in such ordinary domestic duties as cooking, sweeping the house, milking the goats and carrying water. His virtues are well balanced virtues, unmarred by the aberrations of one-sided extremism. Gautama spurned at the throne to get rid of worldliness. Muhammad ﷺ sat on the throne and yet lived the simple austere life of Buddha of the woods. Like Jesus he forgave his enemies, not merely by the word of mouth but in fact, yet he had the balance to show due respect to his foster mother who called on him in later life. Rather than snub her off with “What have I to do with thee” he exclaimed at her very sight, “My mother! My mother!”, stood up to greet her and spread his own mantle to seat her. Like Tolstoy, he lived and worked for the poor and even prayed that on the day of Resurrection, he might be raised in the midst of the poor. Yet he had not the self-forgetfulness of Tolstoy to ignore his own wife and children. “The best of you”, he taught, “is the best of you in his treatment of his wife.” Paradise, he said, lay at the feet of mothers. His wife, rather than complain of any austerity or indifference which he had none was the first to accept his message and thus testified to his loftiness of character: “You are hospitable to the guest and kind to your relations and kith and kin. You help the needy. God will never let you meet with failure.” At the death of his son Ibrahim, his eyes shed tears like a loving father.

Here is a picture that is perfect – a picture that blends all the numerous shades in one harmonious whole. There is hardly a touch of the beautiful or the great which the brush of Nature has not added to it. Muhammad´s ﷺ was not merely the passive, the positive with the negative, in other words, the heroism of a knight with that of a martyr and hence the perfect symmetry of his personality. Buddha of the woods, Jesus of the cross, Tolstoy of the farmhouse, each shows one shade particularly exaggerated and hence they strike at once and capture. Muhammad ﷺ presents a picture where there are not exaggerations, where one shade mellows another, where there are not dots in the background, nothing overdrawn, nothing underdrawn. This, to a trained eye, constitutes a perfect picture.

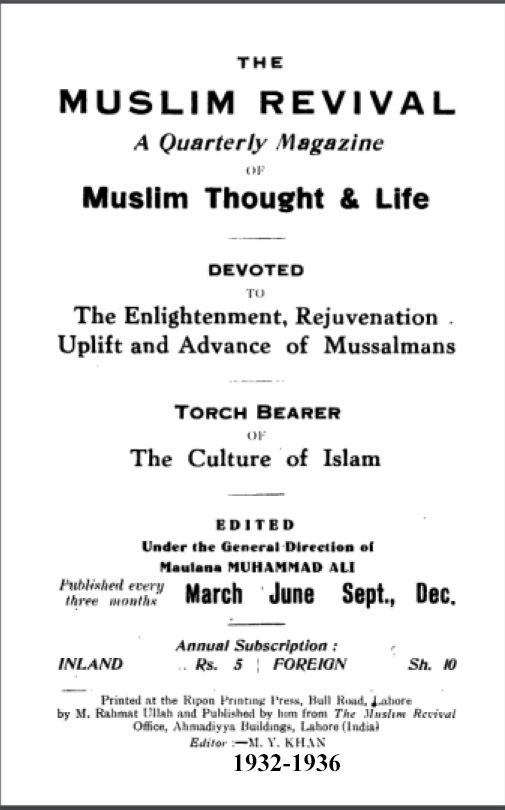

M.Y.Khan

(The Light, Sunday, December 8, 1929)