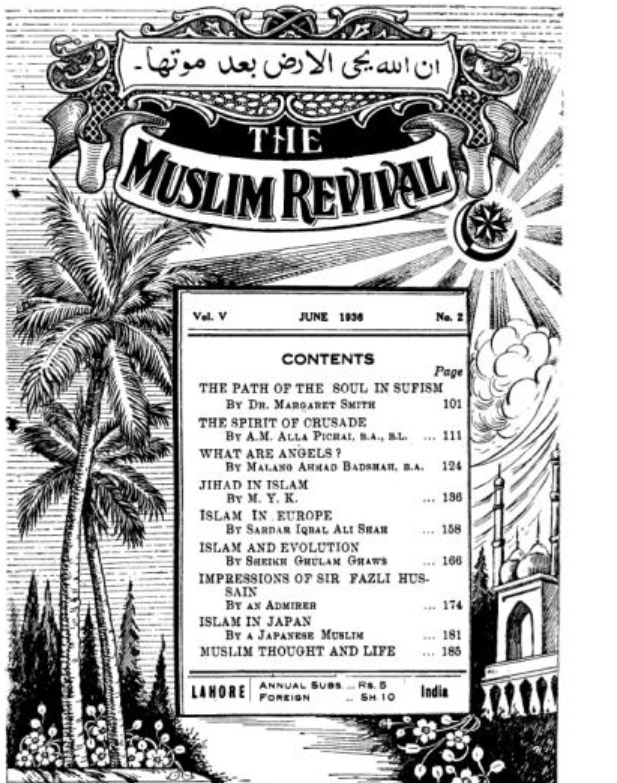

RECONSTRUCTION OF ISLAMIC THOUGHT

HOW Muslim mind throughout the past centuries has been grappling with the changing demands of life necessitated by changing social conditions, and battling to find solutions that would fit in with the categories of thought formulated in the light of the Quran and the Sunnah constitutes an interesting story. One such survey by a Western scholar appeared in our last issue; another appeared in the issue before last. Both are thought-provoking, but both naturally suffer from the handicap that the writers could not but look at the picture through Christian glasses, unwittingly importing therein concepts that were the product of the Christian interpretation of life, having no relevance in the framework of Islamic philosophy. This should underline the need for Muslim scholars with modern education and modern outlook to reconstruct Islamic thought anew in the context of the modern milieu which has brought with it altogether new and far more complicated problems and challenges. The late Allama Iqbal conceived this imperative need of the times, and even set the ball rolling in that direction in the form of his six lectures that were compiled in a book of that name, The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam.

One basic thing in Islamic thought which distinguishes it from most other religions, especially Christianity, is that it does not bifurcate human life into this worldly and other-worldly, into temporal and religious, into secular and spiritual. Islam looks at life as one unbroken stream, the mundane and the spiritual being both blended into a single process, both equally indispensable for the growth and development of the human personality and for that matter the shaping of his destiny.

The Quran has adopted the parable of the “tree” to give an idea of the subtle processes involved in this growth – processes which in modern parlance are considered the properties of organic life, of which change, growth and development are essential features. If rooted in the concept of God, the organism thrives and flourishes and bears good fruit; devoid of this root, it leads to stunted growth and instead of good fruit, it bears only thorns and thistles.

The early history of Islam is a striking illustration of the first. Rooted in faith in God it blossomed into the most humane culture and civilization known to history. It gave birth to a social order of which human equality and social justice were the cornerstones from which, in the words of the Quran, flowed blessings to the whole of mankind. That was the significance of the Quranic description of the Prophet ﷺ as Rahmat-ul-Lil-Alamin, “Blessing unto mankind.”

A striking illustration of the second kind of tree is the present-day Western civilization. Nobody would deny its great achievements in the domain of scientific knowledge and technology, thereby ushering in an era of unprecedented plenty and prosperity so far as creature comforts are concerned. But not its best admirer would say that it has really added to the sum-total of peace and happiness of mind. Having cut adrift from the roots of life in God which secularisation of State connoted, it has ended in robbing man of real peace and happiness of mind. In the individual life this is reflected in broken homes, in the rising percentage of suicides, in the multiplication of mental hospitals, in the spread of teddy-ism, in the social life in the class war and international tensions.

The writer of the article in the last issue arrived at some fantastic conclusions concerning Islamic political philosophy. There is no room, he says, for individual rights in the Islamic system, of which doing the will of God is the keynote. Islam bases the whole of social structure on the concept that man has been created for the highest imaginable destiny – that of being Khatifatullah, vicegerent of God on earth. The concept of individual rights in the West is but a reaction against the usurpation of those rights by the Church in the field of religion, and by the feudal lord in that of’ material well-being. This kind of conflict simply does not arise in Islam where all human beings, the rulers and the ruled, are equal in the eye of God, and where there is no monopoly of religion by a priestly hierarchy.

The other most fantastic conclusion drawn is that in Islam there is no such thing as moral virtue in the objective sense. A Muslim has to be honest and truthful, not because these are moral virtues, but because these have been enjoined by God. Likewise, he must not commit murder, not because it is morally bad, but because God has forbidden it. This kind of hair-splitting forgets that in Islam God’s will and moral excellence are identical.

There is no denying the fact that Muslim thinking itself has been the victim of much confusion, and even in this year of grace 1964 we are still discussing what the shape of an Islamic state must be like, even such elementary things as who is a Muslim, who not. There can be no denying too that after a brief spell of glamour on the firmament of history, the Islamic spark lost much of its glow, and a faith that made its debut as a life-force lost the throb of life and became a stagnant backwater, whereas the West; throwing off the yoke of both the Church and the feudal lord forged ahead from strength to strength, and became the nerve-centre of the world’s life forces. It should be the business of our research scholars to address themselves to tracing the causes of this decline and decay and prescribe a cure for this universal paralysis that overtook Muslim thinking and Muslim body politic.

The root cause, it would seem, lay in the fact that for the organic concept of the Quran was substituted the organisational concept of the jurist. Instead of using the Quran as a source of inspiration, it was subjected to the analytic dissection, to meet the exigencies of life’s new situations as they arose. To dissect is to murder in biology as much as in religion. A rose ceases to be a rose when torn to pieces for laboratory purposes. That is what the jurist did to the Quran and in the process, lost hold of its main purpose the breathing of faith into human heart. The corpus of the Sharia laws that they built up, of course with the best of intentions, proved in practice, to be the grave of Islam as a life-force The spark of life which Islam meant was smothered under the whole heap of the Sharia-laws, which came to be universally taken as substitutes for the real stuff.

The real stuff lies in the spark of faith in God, the root of the Quranic parable of the tree. Early Muslims who came in direct impact with the Prophet ﷺ caught that live spark, like one candle lighting another, and that is how a new force was generated and released. Subsequent generations shifted the whole emphasis from a live contact with God to theological hair-splitting. The result was the substitution of scriptural lore for the live spark of faith which comes only through direct contact with the Source of all law. In one word the organic process of the Qur’anic parable of the tree was replaced and lost in the organisational superstructure of the jurist’s dialectics.

The Ahmadiyya Movement is an attempt to rediscover and recapture that live spark underneath this whole superstructure built up during the centuries – the spark of direct contact with God. Once that contact is re-established, all the rest – political institutions, economic system, social justice – simply follows as a matter of course, and human life, in both the individual and social spheres, is set on an even keel, ensuring smooth flow, peace and tranquillity.

M.Y.Khan

(The Light – October 8, 1964)