MAN AND HIS DESTINY IN ISLAM

THAT the Western mind should have laboured under all sorts of fantastic misconceptions about Islam in the Middle Ages, steeped as those times were in ignorance, superstition and fanaticism, is understandable. That, remnants of that ignorance should still persist in some intellectual quarters in the West in this mid twentieth century, however when the other side of the picture from the correct Islamic sources has been made abundantly clear, is hardly excusable.

A recent instance of this misconception comes from no less a scholarly quarter than the Professor of comparative religion in the university of Manchester, Dr S. G. F. Brandon. In a book under the title, Man and his Destiny in the Great Religions, he brings a wealth of research and scholarship to bear upon tracing the emergence and growth of these concepts in human societies in the remotest antiquity, right up to the Palaeolithic Age, but when he comes to discussing these questions in the light of the Islamic teachings he falls into the same erroneous impressions that vitiated the Christian thinking about Islam in the days of ignorance.

“Man, the Creature of an Inscrutable God” – this is how he subtitles his Chapter VII, which he devotes to Islam. And this is how he winds up the whole of his findings:

“Nevertheless, it would appear that, despite all the tendencies of popular faith, and all the refinements and subtlety of Muslim theological and philosophical thought as well as the witness of Muslim mysticism, the essential Weltanschauung (a particular philosophy or view of life) of Islam remained that which had originally come from ancient Arabia, transmuted by the genius of Muhammad in terms of his own experience and intentions, namely, of man as the creature of an omnipotent deity who predesignated him to eternal bliss or damnation according to his own inscrutable will. To the service of this god man could only submit himself, but the very ability to do this depended absolutely upon the divine favour: “If We (i.e. Allah) willed, We should cause to come to every soul its guidance; but true is the saying of Mine, ‘Assuredly I shall fill Hell with jinn and men together.”

This sums up this distinguished Professor’s reading of the Qur’an as to the place of man in the scheme of creation, his relationship to God, and his future destiny after death. The Prophet’s ﷺ whole conception of God, he tells us, was derived from his social and cultural environment something of an Oriental potentate on a magnified scale, man being just a puppet in His hands, a plaything of His whims and fancies. In support of this he quotes some Quranic verses, including the above-mentioned, which speak of everything having been decreed by God beforehand, even such matters as whether one is going to receive the right guidance sent through prophets or reject it. Islam means submission to God’s will, but, he argues, how at all can he do so if God’s decree has already gone against him? He also quotes verses to support his theory that the concepts of man’s state after death, of bodily resurrection, of heaven and Hell, as given in the Qur’an are also derived from Arabia’s cultural traditions in this respect. Resurrection was considered to be physical, and so were the pleasures of Heaven and the tortures of Hell. The word Allah for God was also borrowed from the cultural milieu of pre-Islamic Arabia in which the Prophet ﷺ was born.

All these conclusions are only a repetition of the stock charges of Western criticism of bygone days against Islam, which have been due to misinterpretation of certain Quranic verses. Translations of the Qur’an by Western scholars blindly copied one another in thrusting on these verses a sense of their own, and on that data, proceeded to find fault with Islam as reducing man to a mere plaything in the hands of an omnipotent deity used to wielding arbitrary power without any rhyme or reason, like a despotic potentate. The topical of these verses is:

“Allah leads astray whom He wills and guides whom He wills. So let not thy soul waste itself in sighs because of them; verily Allah knows what they do.” Quoting this verse, the author goes on to comment:

“For such who have been misled by Allah, there is, according to Muhammad, no hope: Nay, but those who have gone wrong have followed their own desires without (revealed) knowledge. So, who will guide those whom Allah has sent astray? For them there are no helpers. And the arbitrary character of Allah’s action in all this is clearly brought out in Surah xxxii, .13: “If We (i.e. Allah) willed We should cause to come to every soul its guidance; but true is the saying of Mine, ’Assuredly I shall fill Gehenna, with jinn and men together.”

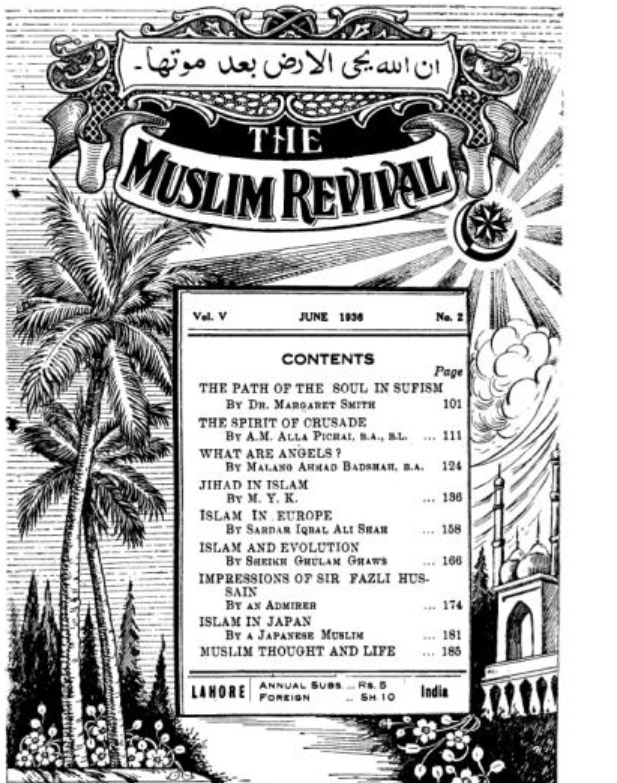

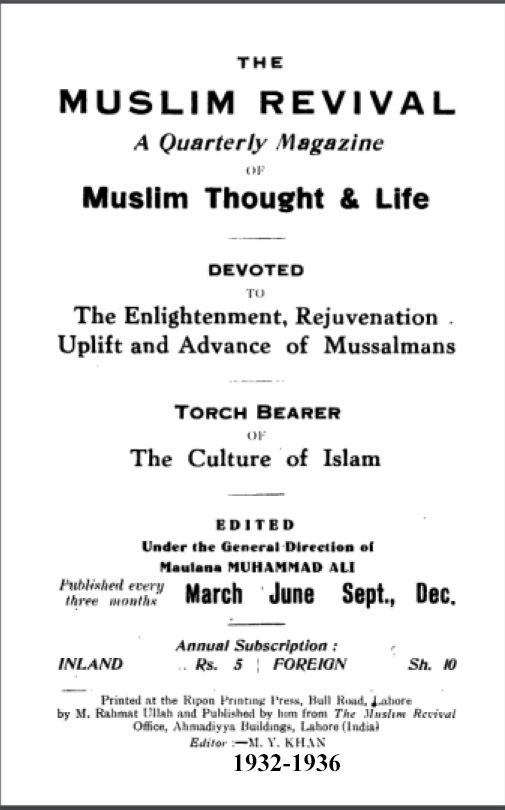

If instead of relying on Bell’s translation of the Qur’an, as the author has done, he had taken the trouble to consult Maulana Muhammad Ali’s translation, he would have realised that the fault lies with the above arbitrary sense thrust on these Quranic verses by Western scholars whose one obsession seems to have been to show off the superiority of the Christian concept of God as Love vis-a-vis the Islamic concept, which, consequently: they painted as arbitrary and capricious, with man being just a plaything to be dumped in Heaven or Hell at His sweet will.

Correctly rendered this very verse quoted by the author demolishes the whole of his theory as to God’s arbitrary dealings with man. The opening words of verse 32: 13, if we willed do not mean that Allah did not will that every soul should receive guidance; it means if God were to force His will on man, he would have forced guidance on every soul. But that is not how he deals with man. He has left him quite free to choose between the right and the wrong ways. Any objective student of the Qur’an cannot possibly miss that freedom of choice between right and wrong is the very burden of the entire message of the Quran. As a benevolent Providence who takes good care to supply all the basic needs of man, God sends His guidance through His prophets for the spiritual growth and development of man. But having sent that guidance He leaves it entirely to man’s own free choice whether to accept that guidance or reject it. “We have shown man the way; it is up to him to accept or reject it” – says an explicit verse. As for those who reject it, His law is that the evil ways which they choose for themselves despite Divine guidance and warning, will inevitably land them into a life of anguish and torture which the word Gehenna (Hell) connotes. That is the correct significance of filling Hell with men and jinn – i.e., the first meaning the common man who chooses to ignore Divine guidance the latter the leadership (Jinn) who mislead the common folk. Allah’s guiding and misguiding, therefore, is not to be taken as an arbitrary action; it is an inevitable sequel to man’s own action in accepting and following God’s guidance or rejecting and opposing it.

A moment’s close examination of this very verse quoted by the author should have sufficed to reject such a view. It clearly states that those who have gone wrong have done so because “they followed their own low desires”, ignoring the guidance in the “revealed knowledge” given to them through prophets. The correct significance of the words, Who will guide those whom Allah has sent astray, therefore, is that those who turn their backs on God’s guidance and follow their own low desires, bring about their own doom in going astray. They, not God, are the agents of their own misguidance. Since this takes place according to the law of God that whoever follows His light will get that light, whoever will reject that light will be denied that light, it has been described as God’s judgement.

It is hardly a fair comment to take detached texts from the Qur’an, and generalise from them, ignoring the main theme and trend of the Book. A scholar of comparative religion like the author surely should have found much in the Qur’an to give him a different idea of the status of man in the providential scheme. The creation of man forms a very conspicuous theme of the Qur’an, heralded by God Himself in the words: “I want him to be My vicegerent on earth”. This is certainly a far cry from the relationship between God and man which the author has read into the Qur’an. This is, however, a big subject by itself, calling for a fuller treatment. The truth of the matter is that the concepts of man’s place in the universe, his relationship to his Creator, what becomes of him when death overtakes him, as given in the Qur’an are rooted in the realities of life as reflected in the working of the whole of the universe. They are the only concepts which, unlike those found in so many other religions, are not the projections of man’s own mind; they bear the hallmark of the testimony of the handiwork of God which the universe is. Indeed, the Quranic concept of God is writ large on the face of the whole of the universe. We hope to revert to the topic in a subsequent issue.

M.Y.Khan

(The Light – January 16, 1964)