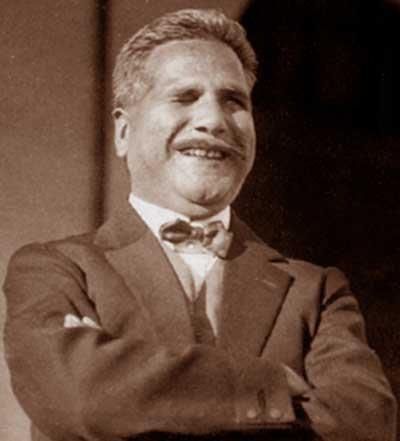

Iqbal as I knew him

By Muhammad Yaqub Khan

(From The Civil & Military Gazette, Friday April 21, 1950)

Iqbal was the most accessible of men. One had only to step aside from Mcleod Road and walk in to find a ready welcome. At the appearance of even the humblest he would descend from the clouds where he usually dwelt and talk for hours on end on the most matter-of-fact things of life.

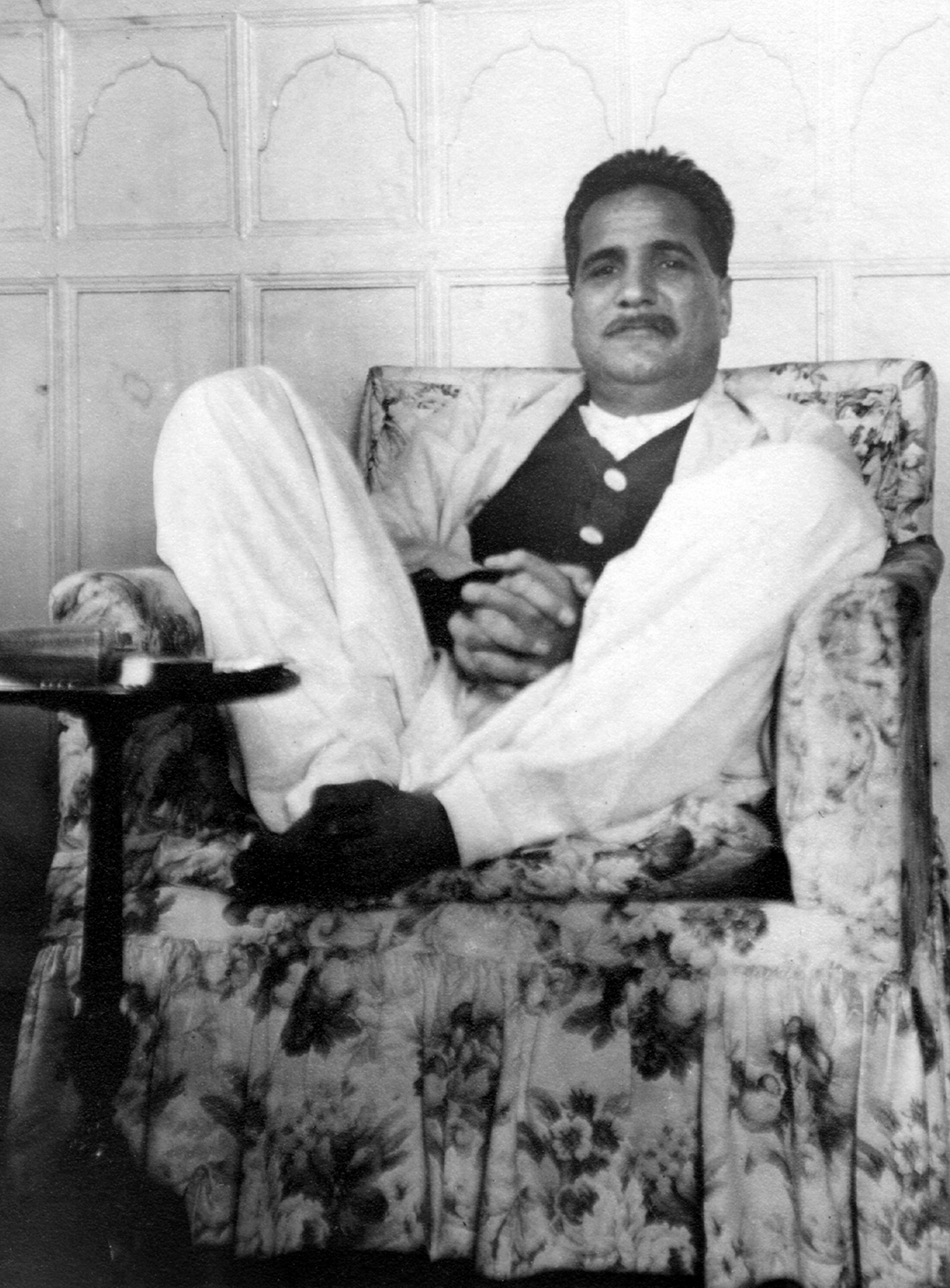

Clad in an ordinary dhoti and a half-sleeved jacket, reclining against a pillow on his charpai, with a huqa as his unfailing companion by his bed-side; a visitor or two dropping in every now and then and quietly taking the chairs that Ali Baksh always had ready for them by the poet´s side – such was a common sight on summer evenings which he spent on the small terrace by the side of his drawing room.

The poet needed only a remark from a visitor to switch on his mind and make him plunge into a conversation which was mostly a one-way traffic, he doing all the talking, the visitors all listening. The talks covered a wide range of topics from the Round Table Conference or the Moral Rearmament Movement to a strike of tongawallas or the industry of shoemaking. He had something to say on each and every topic. These talks continued till late at night, the only break being the dish of dalya which his “man Friday” brought for his master´s frugal supper. And when the visitors rose to say good-bye, they found that many hours had slipped by unnoticed. To sit in at one of these talks was an education; for the evening discourses might aptly be called the unconventional academy of Iqbal.

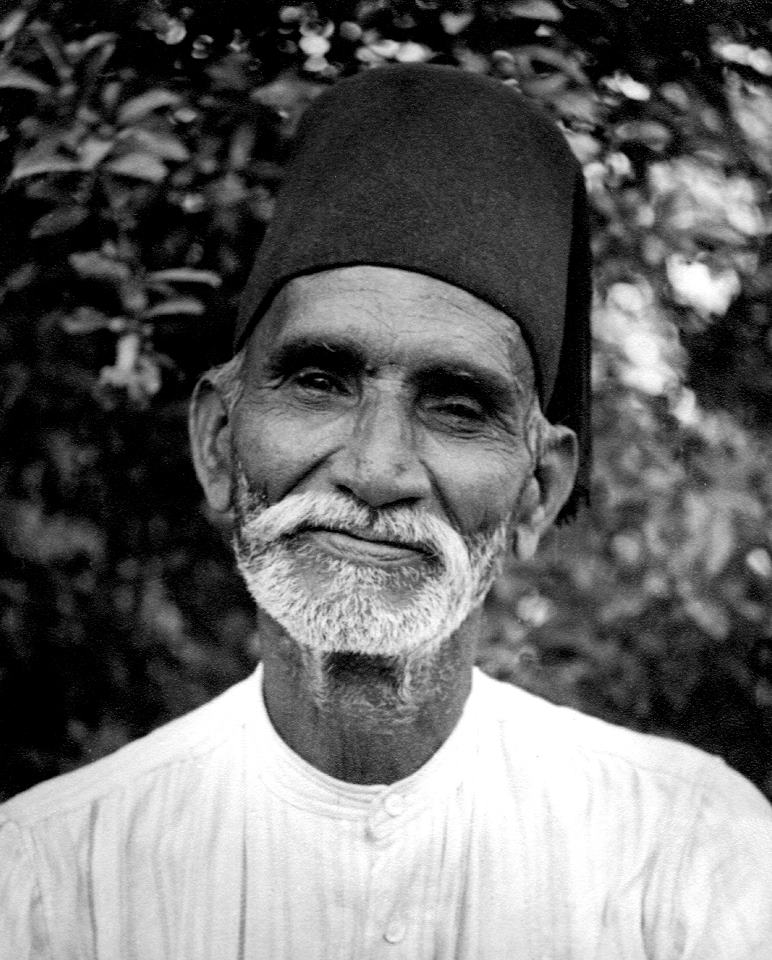

Ali Baksh was the poet´s main contact, his “liaison officer” with the circle of his friends. If he wanted someone, Ali Baksh would go on the errand and no summons was more welcome than his Doctor Sahib ap ko yad karte hein.

The conversation sparkled with flashes of wit and humour. One day I asked him what he thought of a certain political leader – the top-most at the time. “His heart is as black as the face of Mr. So-and-so,” came the reply.

One day Ali Bakhsh called at an unusual hour. “It is very urgent,” he said. I went immediately. A Hindu lady of much charm and beauty had embraced Islam and wanted a Muslim match. It was readily arranged with a Maulvi-like man, unknown to Iqbal, who had recently lost his wife. Within a week the new wife disappeared in dramatic circumstances. As the newly wedded couple were shopping in Anarkali, she said to her husband: “Just wait and I will be back in a minute.” She slipped into a side-lane and was never seen again. When I related this “finis” to a match improvised at his instance, Iqbal remarked: “I should like to see the face of this hirman nasib” (unlucky fellow).

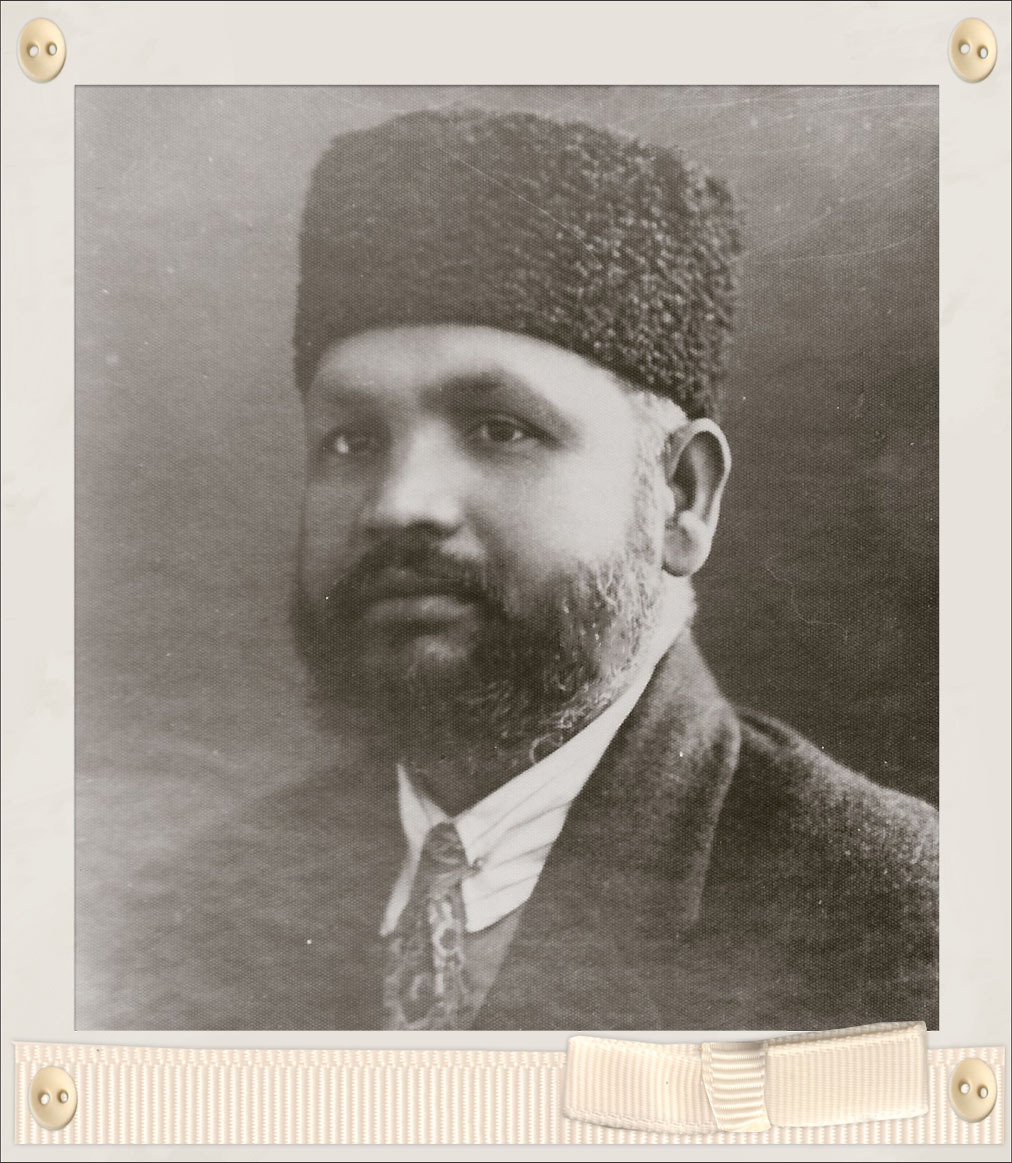

Iqbal was very intimate with the late Dr. Yaqub Beg, a noted physician with a religious bent of mind. He would often call at his place in the town. At one such call I happened to be with them when Azan was called from the neighbouring Mosque.

“Let us go and say prayers,” said Dr. Yaqub Beg, knowing Iqbal was in a hurry and could not stay. “Do you pray just five times,” retorted Iqbal. “With me the rule is: Jo dam ghafil, so dam kafir (every moment away from the presence of God is kufr,”)

An interesting controversy cropped up in those days. The Turkish Revolution had just concluded, and Ataturk was busy reforming things right and left. Salat, the prescribed prayer, was rendered into Turkish. I asked the Poet what he thought about it. He replied that understanding of prayer was not essential. That mattered was the state of mind. That purpose was sufficiently served by the very postures and gesticulations of prayers. Arabic must be retained.

Iqbal showed his intimacy with his friends by taking occasional liberties with them. The following story about the late Sir Shahabuddin, Speaker of the Punjab Assembly, is well-known. When at a dinner party he came dressed in the usual black suit, the Poet remarked:

Chaudhri ji, ki gal hai – ap nange he chale aye ho (what is the matter, Chaudhri Sahib, you have come naked to-night?)

Something similar he once did to his doctor friend, Yaqub Beg, who, out of great regard, had arranged to put him in the presidential chair at a meeting at which he was to speak.

After Dr. Yaqub Beg made a lengthy speech in Urdu, Iqbal got up and said: “If Urdu were to have a few more such patrons, we would soon have to read a funeral oration over it.”

Never will those who were proud to call Iqbal friend forget the intellectual pleasure and the soothing charm of his intimate conversations. And even now, by browsing through his verses, they can relive that pleasure and recapture that charm.

(The requested article was sent to me by The Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., U.S.A.)