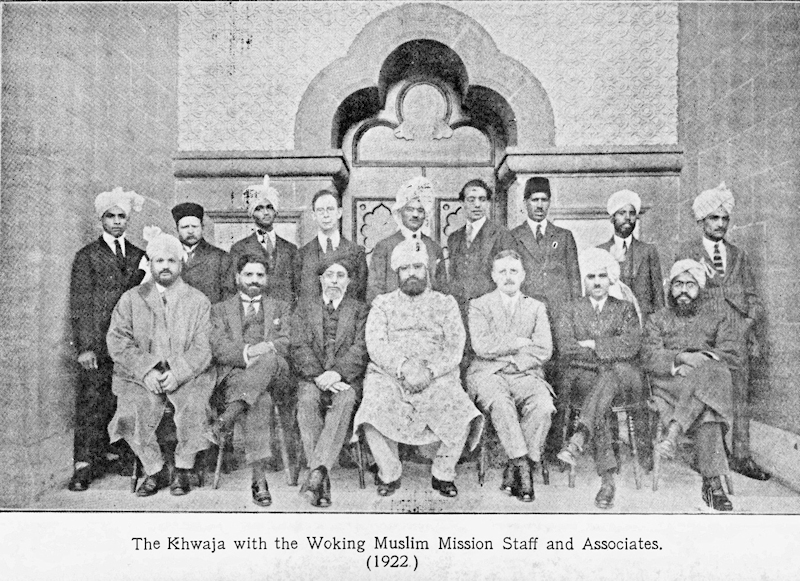

Al-Haj Khwaja Kamal-Ud-Din

The Editor, The Muslim Revival-December 1932

Mohammad Yaqub Khan

Al-Haj Khawaja Kamal-Ud-din, founder of the Muslim Mission, Woking (England) breathed his last on Wednesday, December 28, 1932 at 12:45 A.M. at the age of 62. Inna Lillahi wa inna ilaihi rajiun!

Perhaps it is too early for a due appraisement of the Khwaja´s enterprise in embarking, single-handed, on a spiritual conquest of the West. The final verdict must lie with the future historians. Maulana Sulaiman Nadwi once described the Woking enterprise as one of the greatest achievements of the century. Perhaps it is more. I am inclined to feel Woking is not a thing of a century. It is a land-mark in history. What was the inspiration at the back of it? The same that urged the early sons of Islam to embark on a conquest of Europe and made them burn their boats and plunge their horses into the sea. If the Khwaja were born in those times, his name would have been among such heroes of Islam. The Fates had reserved for him a similar glory but with different weapons – a spiritual invasion of Europe. Woking must therefore be put in the same scales with such like epochs in the history of Islam. Khwaja Kamal-Ud-Din was the Tariq of his day.

Iqbal the poet-laureate of the East sings in stirring strains of the heroic enterprise of Tariq:

طارق چو برکنارہ اندلس سفینہ سوخت

گفتند کار تو بہ طریق خراد خطااست

Who knows that the Iqbal of the 21st or 22nd century may in similar sentiments commemorate the enterprise of Khwaja Kamal-ud-din. It was an enterprise without the clang and clatter of arms. But the spirit underlying it was just the same. Khwaja Kamal-ud-din had no boats to burn but he burnt the boat of his own career and in the same reckless spirit dashed across the seas to accomplish what at the time seemed nothing short of madness. And ever thereafter he was so lost in the struggle that he forgot everything else. Even his closest friends and colleagues came to accuse him of Woking-mania.

There is no part of the world of Islam where the death of Khwaja Kamal-ud-din has not evoked a spontaneous outburst of grief and sympathy. Where lies the secret of this universal charm which his name exercised? The secret is that Khwaja Kamal-ud-din was no longer an individual. He had become an institution and his name conjured up the whole of the Ishaat-i-Islam movement in the West. So thoroughly had he merged his identity in the cause that both in the worlds of Islam and non-Islam his name symbolised that greatest enterprise of the modern age, the Islamization of Europe. In the public mind Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din was Woking and Woking was Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din.

It is not by the number of converts that the achievement of Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din must be measured. To have shown the light of Islam to hundreds of English men and women, from the highest rung to the lowest, is by no means a small achievement. It has opened the way for the Islamisation of the West which was the dream of his life. What is, however, of far greater consequence is the distinct stamp that the Khwaja made on the thought of the West. The Khwaja was no mere dreamer and enthusiast. He was a deep thinker and he had a philosophy of Islam of his own. He had a wonderful knack of putting Islam in a most presentable form, in keeping with the modern mentality and modern requirements. This made him irresistible. The Christian Missionaries were naturally alarmed and “Woking danger” was even talked about in the British Press. But they did not know how to combat the danger. At last they hit upon a weapon. It was “unorthodox” Islam, they said, which Woking preached. “A new Mohammad,” they said whom Woking painted “out of the Christian paint-box”. In a way they were right. They had quite a different picture of Islam and the Holy Prophet in their minds, as drawn by the pen of propaganda. When the Khwaja put before them Islam in its true beauty and unfolded the lovely portrait of the Holy Prophet, they simply rubbed their eyes. The greatest achievement of Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din therefore lies in the revolution which he brought about in the thought of Europe with regard to Islam. And if today men like Bernard Shaw can visualise the Islamization of Europe within a century, the credit in no small measure should go to the Khwaja.

The enterprise of Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din was primarily launched against the West, but naturally it had a repercussion on the world of Islam itself, leading to the revival of faith which, through Western influences was gradually decaying. The Mussalman of Western education, when he saw this rational exposition of Islam and men of high standing from among the ruling race bow to the force of Islam began to shed much of their inferiority complex and to say to themselves that Islam was after all not a thing to be ashamed of. Were it not for this factor, it is sure the youth of Islam, like the rest of the youth of the world would have been carried off their feet by the tide of atheistic materialism which is the order of the day.

“No-sect-in-Islam” was another most conspicuous plank in the campaign of Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din. There is nothing new in it. Sect is the very negation of Islam. Nevertheless the House of Islam presents such a disgraceful spectacle of sectarian feuds. With his penetrating eye, the Khwaja saw that a sect-ridden Islam was not the thing that the West, sick of her own mushroom of sects and subsects, would at all care for. He had therefore to lay all the emphasis at his command on this forgotten aspect of Islam viz., freedom from sects. It was the folly of the Mussalaman that had magnified mere schools of thought into so called sects. As a matter of fact, there were no sects. Islam was all one. And Woking under whose auspices the Sunni, the Shia, the Wahabi, the Ahmadi all met as fellow brethren in Islam, presented a wonderful spectacle of a united Islam which could not but catch the fancy of the English people. This too, though primarily an indispensable weapon for his Western campaign, led to a wholesome revolution of thought in the world of Islam itself. The average educated Mussalman will now have nothing to do with sects. In bequeathing this great principle to the world of Islam, the Khwaja has paved the way for the renaissance of Islam which has already set in.

Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din was born in 1870 and received his education in the Forman Christian College, Lahore. Perhaps the influence of a Christian institution in which he was brought up had something to do with the future developments of his life. Like the average under-graduate of the day, he felt disgusted with the picture of Islam as presented by the common Mulla. The atmosphere of the Missionary College caused him much of heart searching, undermining faith in the truth of Islam. It was even apprehended that through Christian influences, he might be altogether lost to Islam. It was during this period that he was brought into contact with the late Mirza Ghulam Ahmad of Qadian. This was a turning point. Thenceforward he was a changed man. Not only was the flickering flame of faith in him saved from extinguishing. It was so re-kindled that propagation of the beauties of Islam and its Holy Founder became the very food of his soul. After graduating in 1893, he became professor and soon after, Principle of Islamia College Lahore. He took his degree in Law in 1898 and for six years had a flourishing practice in Peshawar. In 1903, he migrated to Lahore and was soon one of leading figures of the profession. He was a fellow of the Court of Trustees of the Muslim University Aligarh and a life-member of the Ahmadiya Anjuman Ishaat Islam, Lahore. It was in 1912, that the supreme call of his life came to him and renouncing the world with all the glamour of rosy prospects, he set out on his historic enterprise to illumine the West with the light of Islam. And ever since his has been a life of incessant struggle in the cause of Islam. And though confined to bed for long years, he seldom allowed himself rest and kept the struggle on, overtaxing his already shattered system for which he ultimately had to pay with his life. I had the privilege often to visit him in his sick-bed and even when his sick-bed had evidently become a death-bed. And when in that state I saw him full of his usual fervour in the cause of Islam, dictating with the same enthusiasm notes on Islam or articles on Islam or a rejoinder to a critic of Islam, he struck me as a wounded soldier on the field of battle, who, though dying by inches was sticking fast to his guns. And such indeed the Khwaja was. A fighter in the cause of Islam, he fought and fought and fought and with his “sword in hand”, as it were, he met his death.

May his soul rest in peace!