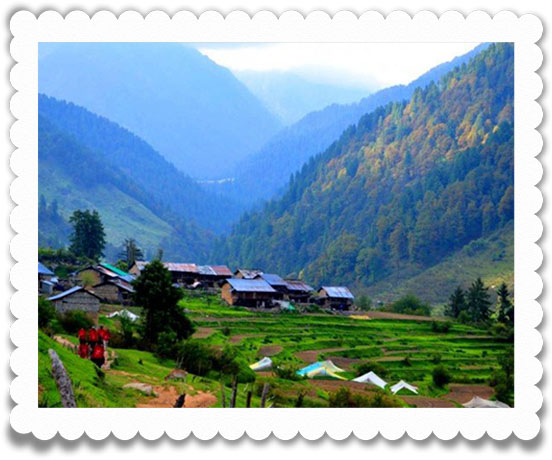

A Week in Dharamshala (India)

If you want to see the India of old, go to some hill district, away from the haunts of civilization. Here in these parts, you find man still living, as it were, in the stone age. The bustle and hurry of modern life is a thing unknown there. Calm and content marks everything – man and bird and beast – and you are reminded of the good old days when Adam delved and Eve span.

Dharamshala is one such place, not the town of course, but the countryside. My business recently took me there and short though my sojourn I made the best of it. I moved from village to village, from hamlet to hamlet, to see men and things for myself. I think some of my impressions might be of interest to the readers of “The Light” especially what I saw there of what passes for religion and hence these few lines.

Like the rest of the hill places, Dharamshala is indeed an interesting relic of ancient India. Population is mainly Hindu, with a bare sprinkling of Muslims. The rigidity of the caste system is perhaps nowhere stronger than here. The high caste Brahman must not touch anything cooked by a Hindu of a lower order or by a woman, even though Brahman. And so, the Rajput must not take things prepared by those below him or by a woman, even of his own order. Then come those wretched people known as the “untouchables”. There are several tribes of these unfortunate outcasts, known as the Batwals, the Sarirs, the Dumna, the Chamar. Not only is anything in the way of edibles touched by them considered unclean for a Brahman or a Rajput, but their very contact is supposed to pollute. Their persons are shunned like plague. No part of their body must come into contact with any part of the body of higher caste of man. This means the greatest sin against religion.

Idol-worship, image-worship, stone-worship and such like primitive forms of worship are still in vogue. As you pass along a mountainous track, you can read the whole history of the religion of these people. On a huge rock by the way side, every here and there, you see engravings of Hanuman and other mythological figures. Figures of big snakes engraved into a big stone is another popular form of worship. In one village temple, dedicated to a certain Devi (goddess), now in ruins owing to one of the frequent shocks of earthquakes with which this part is visited inspite of so many gods and goddesses. I also came across a lion carved out of stone, in addition to the curling snake and the mythological figures engraved in huge slabs of stone. Besides, there is hardly a house where they don´t have miniature idols of their own. And what moved me very much was that thousands of human beings should, in this twentieth century, still be enshrouded in such ignorance and superstition. In their worship of these things of their own creation, they are as devout as a man of any other religion. Perhaps they are more so; for there they have their Hanuman, their snake, their lion, their elephant, in solid stone, right in front of them.

(Mohammad Yaqub Khan)

Editor: The Light-16 dec. 1923.

Stone-worship is also common. One day as I was out on my daily round, my guide drew my attention to a patch of ground, red with blood and strewed with flowers. This again, I was told, was the outcome of religious devotion. The blood, now dried up into a thick crust, was the blood of the goats offered as sacrifices there and so were those flowers there as an offering. I pulled my wits together, but I could not account for the thing. Such sacrifices, I knew, must be offered at the feet of some idol-god or goddess, but there was neither the Hanuman, nor the snake, nor the lion, nor the elephant, nor any other blessed thing that I could see there. What was it for, after all, I said to myself. And my surprise knew no bounds when my guide told me that all this was meant for the rough, unhewn piece of stone lying there. This stone happened to be so shaped that by a very wild stretch of imagination, it might be thought to resemble the head of an elephant. On the top of this elephant-headed stone, there lay another

piece of stone, rather thin and in the shape of huge plate. Was it not some mysterious arrangement to protect that head-like stone from rainfall? Well, then, that stone must be some goddess, of which so much care had been taken. This is how they argue there and that is why they bring their offerings to that uncut piece of stone on the hill side. It is known as “Kunal Pathar” or Plate-stone from the huge plate-like stone which affords shelter to the elephant goddess.

Every village has a few Muslim families as well, but these are no better than their neighbours. They are Muslims only in name. They have no mosques of their own, nor do they know aught about their religion. Even in outward appearance, they have taken after their Hindu fellow-villagers, so much so that you cannot tell a Muslim from a Hindu. In certain cases, the influence is felt even in names. I met one Muslim youth who comes of a very high Rajput family whose name, I was told, was Ihsan Singh. These Muslims are as steeped in ignorance and superstition as the Hindus. Some, I was informed, have taken to the Hindu practice of keeping miniature idols in their household. I was much pained to hear this. Whether any of the so many Muslim Anjumans in the Punjab knew about this degeneration of their brethren in faith and whether, knowing this deplorable state of things, they would care to take any steps to ameliorate their condition – I wondered and still wonder.