Religion And Material Prosperity Not Incompatible

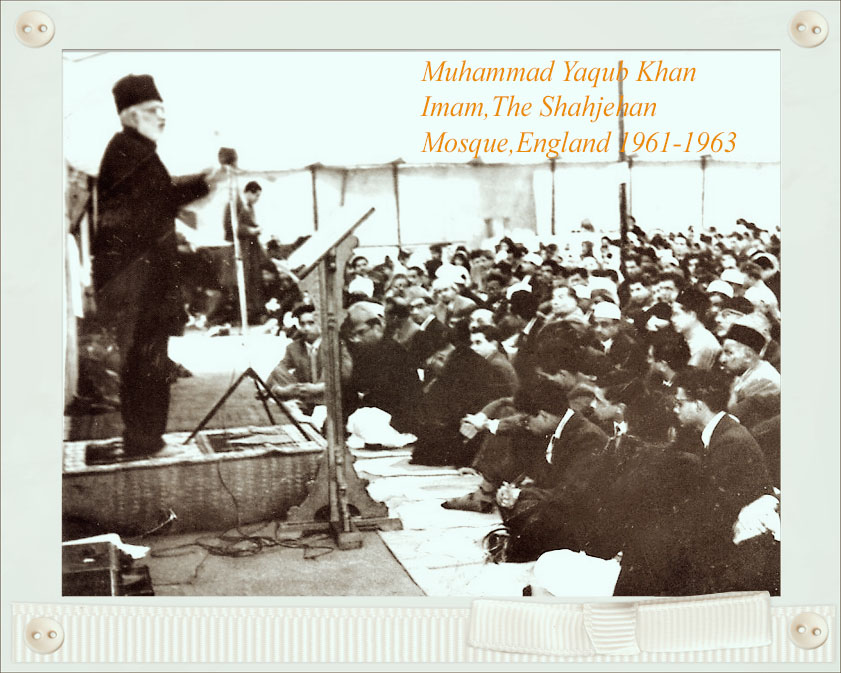

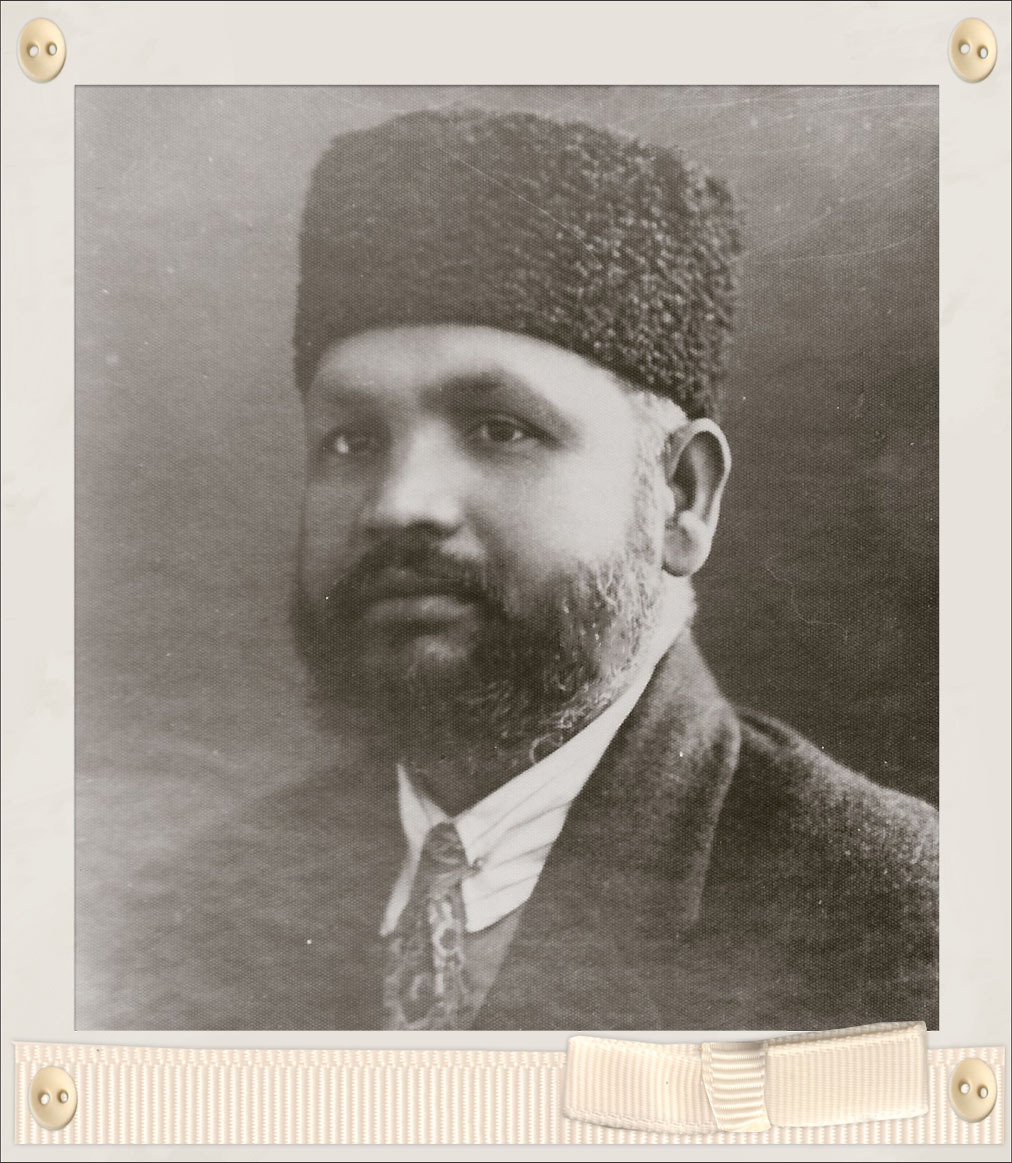

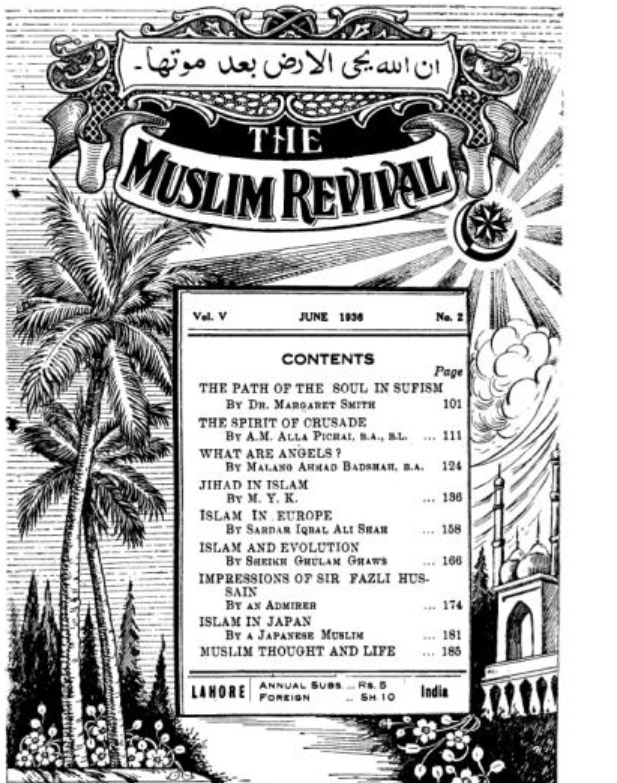

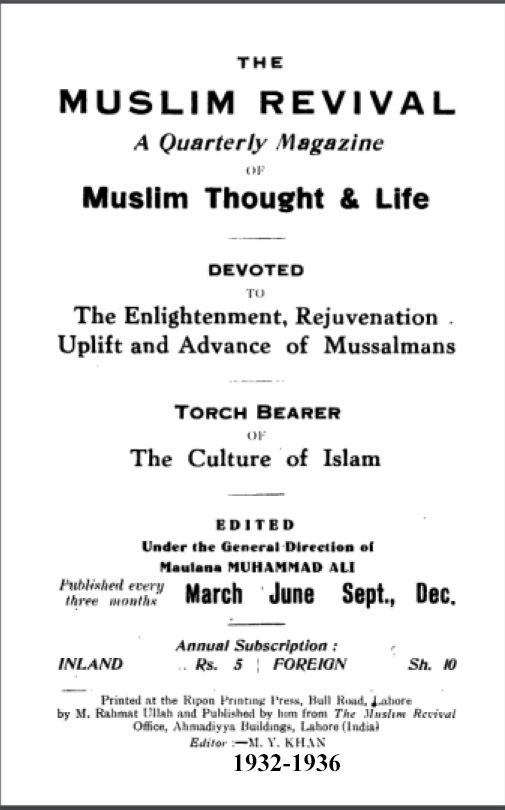

Muhammad Yakub Khan

(Imam, The Shah Jahan Mosque, Woking, England,1961-1963)

“Men of Faith to have a two-fold Paradise: A Paradise on earth and a Paradise in Life-to-come” – Says the Qur`an.

A question which exercises the minds of most thinking people is the apparent clash between the demands of the flesh and those of the soul.

On the one hand, there is the pressing demand to provide daily bread to one´s children, and on the other the call of religion to take care of the well-being of the soul. The demand of daily bread, they argue, must naturally take precedence. It is only when this elementary demand has been satisfied that man can be expected to seriously think of religion and its demands. The Communist way, therefore, they conclude, supplies the only sensible answer to the problem of life, which is basically a problem of bread.

There is much force in the above contention. The apprehension, however, that these two demands of human nature are mutually inconsistent is based on a misconception. No religion, worth the name, would disregard the demands of the flesh, and yet expect man to explore the life of the spirit.

Even Buddha, whose religious system, as in vogue today, is identified with the renunciation of life, had to return to the so-called worldly life and seek spiritual fulfilment in the service of fellow-men.

Jesus, whose Gospel is erroneously construed to encourage renunciation of life, did not altogether rule out the demand of man´s physical life. When he told his disciples, “Seek ye first the Kingdom of God and His justice and all these things shall be added unto you,” he only wanted them to put first things first. He never deprecated the good things of the world or their pursuit by man. Ascetism, which the Church subsequently introduced as a means to achieving Godliness, has been described by the Qur´an as an innovation that was never enjoined by God.

The philosophy of renunciation of life is rooted in the misconception as to the duality of the human nature. Its two component elements, the flesh and the spirit, were conceived to be something perpetually antagonistic.

The next logical step was that if man wanted to develop spirituality, it could only be done by crushing the promptings of the flesh. The thousands of naked Sadhus in India, undergoing voluntary physical tortures, and the institution of monasticism in Christianity, are the products of this misguided zeal to reach God by trampling upon the physical body He has given us. For that very reason in the Middle Ages, the Church discouraged even taking a bath as something irreligious, inasmuch as it implied the satisfaction of the flesh.

Islam, among many other reforms, dealt a death-blow to this erroneous view of human nature. The flesh was as much the gift of God, it taught, as the spirit. The two were in no way incompatible: they are complementary. But for the flesh, there would be no life of the spirit. The flesh is to the spirit what the soil is to the seed. But for it, the life of the spirit would never germinate, grow or blossom.

There was absolutely nothing wrong with this world, nor with the human nature, proclaimed Islam. Man was the vicegerent of God on earth, and he was here to work out those wonderful Divine potentialities within him. This earthly life, declared the Prophet ﷺ, was a tillage for the life to come. Man was the architect of his own destiny, this worldly life being the essential material to build it with.

The Qur án declared that for a man who leads a life in the fear of God, there is a twofold Paradise – a Paradise on this earth, and a Paradise in the life to come.

(The Islamic Review, April 1959)